FOUR MILLION WORDS ... AND EVERY ONE A GEM

- Jim Withers

- Oct 10, 2023

- 12 min read

Updated: Oct 11, 2023

by Jim Withers

My whole life did not flash before me the day that Pete, Ralph and Wayne leaped into the muddy swimming hole and saved me from drowning.

Then again, I can’t be sure. It happened maybe 60 years ago, so I suppose it’s possible I did experience that trope about people in near-death situations seeing their entire existence reduced to a split-second montage. All I can remember with certainty was my sheer panic and that I swallowed a lot of water while flailing away. Even my rescuers can’t agree on exactly what went down – other than me several times.

Shortly before I turned 75 this summer I got another glimpse into my mortality, albeit a much less dramatic one than occurred at that bottomless, spring-swollen river so long ago.

Seated in front of my home computer, I found myself suddenly looking into the void, a world which apparently did just fine for eons before my arrival and which will, no doubt, somehow cope without me for eternity after I’ve checked out.

In this summer’s scare, I did sort of see my life – or at least most of it – fly away like the months on a wind-blown wall calendar in an old black-and-white movie. The spectre of my nonexistence arose after I spent a few hours over two days conferring on the phone with no less than four tech-support people toiling in far-away places. My desktop had seemingly died, and it dawned on me that all the king’s horses and all the king’s men, let alone all the tech-support people in far-away places, were never going to resuscitate my iMac. I’d have been OK with that because you can always replace gizmos, but it was what the iMac housed – my diary – that concerned me.

Had I backed up my data on my desktop? they asked. Ah, no – at least not knowingly.

I’m not proud of it, but I’m a Luddite. And it’s not just an age thing; many of my fellow boomers have embraced the digital revolution with all the zeal of a convert. But not me. As with swimming – I still haven’t mastered any strokes – I’m out of my depth when it comes to gigabytes, browser cookies and remembering passwords, and I didn’t have enough fluency in computerese to totally comprehend what my would-be techie rescuers were telling me. Nor could I clearly communicate what was happening – or not happening – at my end. And so we soldiered on in mutual incomprehension, what the Chinese call “chicken and duck talk,” to no avail.

For days I felt the sense of loss that an acquaintance of mine must have experienced when someone stole her car, in which she’d left the diary she’d started in her teens and which included intimate details of her affair with a famous person. I don’t know about the car, but she would never see her diary again.

My journal dates back 48½ years – nearly two-thirds of my life – and until my iMac appeared to go into cardiac arrest, I didn’t fully realize how much I valued it. As Joni Mitchell sang, “Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone …”

Like an old friend you take for granted, my diary was just something I regularly attended to, like brushing my teeth or feeding the cat. Until recently, I rarely read any of it.

Sometimes my journal was where I’d go to vent, a kind of cheap therapy in which I could get things off my chest, or do a one-man debriefing on how my day unfolded. Other times, it was where my inner reporter came to the fore. My life-long love of reading, writing and storytelling had led me to a career in the newspaper business, and now, a dozen years into retirement, I continued to have an obsessive need to record what was happening in my world. We all have multiple identities, and one of mine is that of chronicler, the guy who is rarely the life of the party and more likely to be the wallflower, quietly observing and surreptitiously taking notes. Once a reporter, always a reporter.

With my diary locked inside my apparently dead iMac like an irretrievable buried treasure, I felt like I’d lost my life savings – and, in a way, I had.

Fortunately, after a couple of days in which my poor wife had to endure language rarely heard around our house, a saviour materialized in the form of a tattooed, ball-cap-wearing 43-year-old guy who lives with his British bulldog. Found online by a tech-savvy friend, Benjamin does computer repairs out of his second-floor apartment a short walk away.

Laid-back Benjamin seemed bemused by my inability to speak the lingo, but he clearly relished the challenge of getting into my “vintage” iMac. My hard drive was not defective, but corrupted, he explained, adding that the external drive – “ ‘the little black box,’ as you call it” – had saved all my desktop data until a few days before the iMac crashed.

A day later, he had worked his magic.

“Benjamin, you’re a life-saver,” I exhaled while petting his dog on my way out.

***

When I was an adolescent, I started keeping diaries a couple of times, but quickly abandoned them, perhaps out of concern that my parents’ or sisters’ prying eyes might gain access to more of my life than I was willing to share. Or maybe diary-keeping wasn’t a priority compared with, say, my new-found interest in girls.

On New Year’s Day, 1975, though, I launched yet another personal journal, and third time proved to be the charm. Little did I know it, but 315 years earlier – to the day – Samuel Pepys began what would become one of the world’s most celebrated diaries.

Pepys was no Shakespeare, but his million-word, 9½-year journal, with its engrossing insights into 17th-century Restoration England, and the immutability of human nature, became for me an inspiration. Written from the perspective of a civil servant who rose to become chief secretary to the Admiralty, Pepys broke new ground as a diarist, making himself the centre of a much larger narrative than just his life. Pepys’s diary is a vivid tapestry, weaving in social history, major political issues of his day, grim eyewitness accounts of public executions and the carnage caused by the Great Plague of 1665 and Great Fire of London a year later, along with Pepys’s commentary on all manner of subject. The man had an eye for detail and lived large, with insatiable curiosity and appetites, and occasional pangs of remorse over his often-sordid behaviour.

Like Pepys, I began my diary at the age of 26. And while I’d never compare mine with his masterpiece – for starters, my peccadilloes would pale in comparison, and I write from the perspective of someone who had a modest career in newspapers, not an influential government official who met with kings – I’ve also tried to take an all-inclusive approach to diary-keeping. Against a turn-of-the-millennium backdrop, I tried to capture what it was like to witness the final days and nights of the golden age of newspapering.

Pepys ended his diary in 1669 over fears he was going blind. To avoid having anyone read his often-salacious narrative, he wrote in a coded form of shorthand. Fortunately, for history lovers everywhere, his manuscript was found, deciphered and published two centuries ago.

I don’t know what prompted Pepys to keep a journal – nor for that matter why I started mine – but I think another great diarist, Anaïs Nin, comes as close to the answer as anyone:

“We write to create a world in which we can live. We also write to heighten our awareness of life. ... We write to taste life twice – in the moment and in retrospection.”

It wasn’t until 1977, when I travelled to Europe for the first time, with a widow 16 years my senior, that my personal journal turned into something more than just a bare-bones account of day-to-day life. Escaping my workaday world for three weeks, I felt such a sense of adventure that I wanted to record everything. I didn’t think I’d ever experience anything quite like this again – there’s only one first time for everything – so each night I scribbled frenziedly into a notebook about what Lorna and I had experienced. This included:

*me driving “on the wrong side of the road” in her native England, and stopping at the first pub for something to steady my nerves after travelling only about two blocks from the car-rental place;

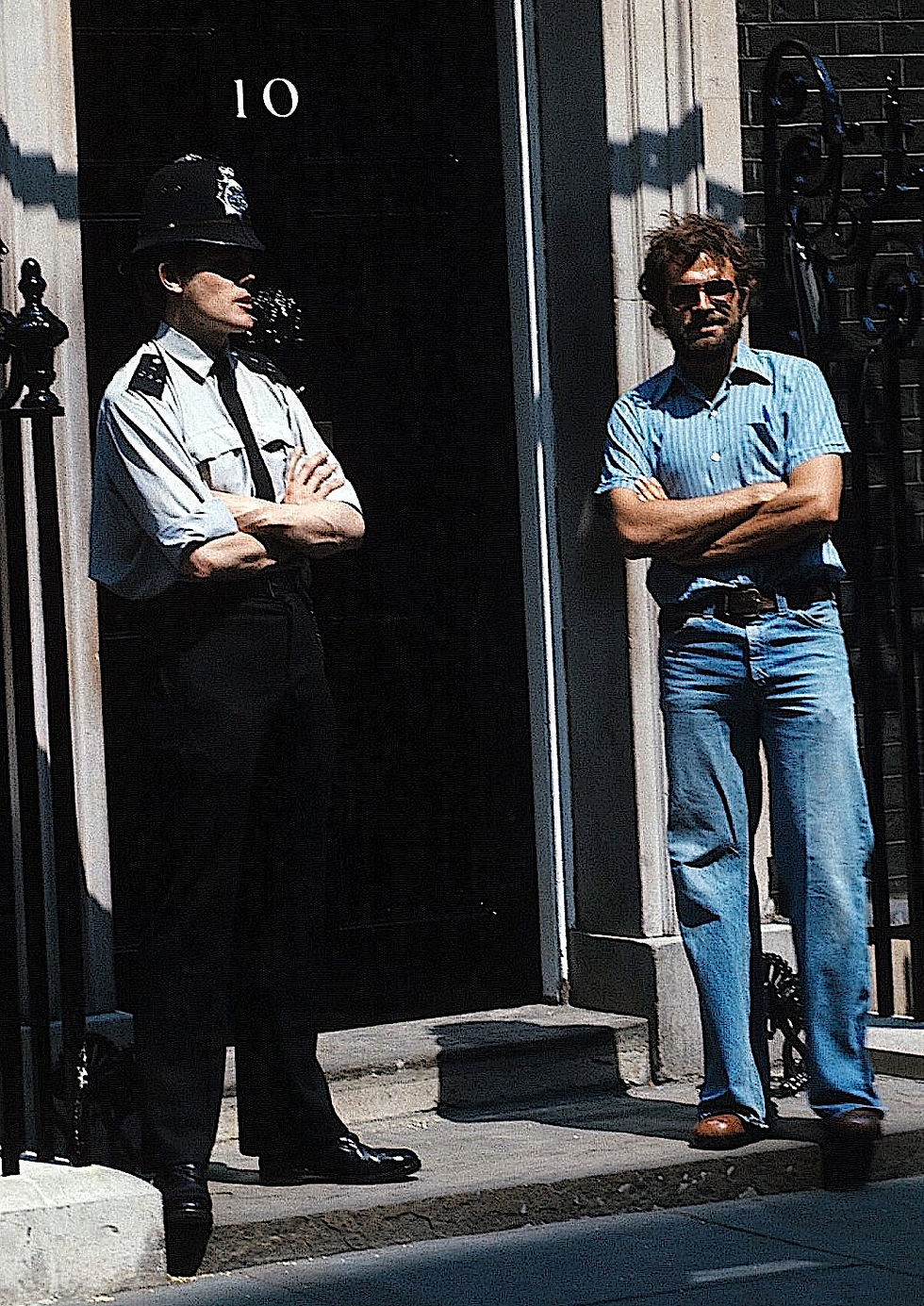

*me posing for a photo in my hippie locks and faded bell-bottom jeans on the doorstep at 10 Downing St. (when such a thing was possible) and being gently scolded by a tall bobby (“Please don’t stand on the step, sir”);

*Lorna and I clambering into an abandoned World War II army tank rusting in a grassy field in Alsace; and

*me listening in on a couple’s conversation at a table next to ours in a restaurant in a Swiss village:

Woman: “Aren’t you happy for me now that I’m over my four-year problem?”

Man (unconvincingly): “I am happy for you.”

(I’ll never know what she meant by “four-year problem.” Was it a physical or mental disorder? Was it a euphemism for an affair one of them had, and something they wanted to keep from the two children seated with them? I included it and more of their conversation in my notebook because I thought a day might come when I could use it as a scene-setter for a short story or novel. It was possibly the beginning of my becoming a shameless eavesdropper, stockpiling snatches of random conversations, similar to the way my garage-owning father stored nuts, bolts and scraps of metal in a wooden box in case they might at some point prove useful.)

I was hooked on travel, and from then on, be it trekking in Nepal, aboard a camel in Morocco, living briefly with locals in Haiti or on a solo road trip through a stretch of desert-scape on Route 66, I take notes with abandon whenever I’m on the move. The whole point of travel is to break loose from the mundane, to experience new things, and accounts of these experiences occupy huge swaths in my journal. After my first European escapade, I globe-trotted frequently over the next quarter of a century, harvesting diary entries from trips to add flavour to the travel stories I’d write for the newspaper.

My journal gradually started to include more and more local colour, too, about what I saw and heard on the métro, for example, or at the laundromat and, especially, working evenings on the news desk. I recorded examples of the banter that would prevail early in the shift, the way tension would build as deadlines approached, and the wit and wisdom we shared post-shift at our watering hole as we retold favourite war stories about the larger-than-life characters who, despite all their smoking, boozing and philandering, were somehow able to write or edit news stories night after night.

An inveterate note-taker, I always have a pen and piece of paper with me. Sometimes my notations are just inconsequential vignettes:

June 14, 2023: “Fuggedaboutit! … It’s too big.”

Striding along the crowded sidewalk near Sainte-Catherine and Atwater, I turned to see who had bellowed. It was a homeless-looking man, and it took me a second to realize he was admonishing a seagull that was gamely trying to fly away with a discarded baguette.

Other times, my diary entries are darker:

Feb. 8, 1980: Around midnight, riding in a cab on my way home from work (at the Ottawa Journal), I heard the crackling voice on the taxi radio of another cabbie somewhere else in the city:

Cabbie: “Can you send a police car to ...?”

Dispatcher: “What do you need one for?”

Cabbie: “There’s a guy here and he’s pointing a gun at me.”

Despite my ineptitude with technology, I appreciate what computers can do. And while it wasn’t a smooth transition for me to go from working with typewriters to word processors to doing page layouts on computer screens, I decided in 1997 to start writing my diary on a keyboard. It was a game-changer. Since moving from cursive to digital, my word output has increased maybe eight-fold to about 130,000 annually, the equivalent of a novel a year. I no longer suffered from writer’s cramp, as I had in my cursive days. And, unlike with my hand-written journals, I was now able to do name or word searches whenever I looked for entries about particular people or events. After going digital, I gradually incorporated my 22 years of hand-written journals into my computer diary, and while I was at it I also typed in some of my favourite letters from family and friends, and pasted in several email conversations. Everything was now housed under one easy-to-access roof.

Using the computer’s “copy-and-paste” function I went on to create a commonplace book, an addendum to my now-massive diary. Described by the Canadian Oxford Dictionary as something in which “notable extracts from other works are copied for personal use,” my commonplace book is a kind of digital scrapbook in which I not only list favourite quotes and song lyrics, but in special files, like the one I labelled Voices, I store vignettes that I’ve copied from my diary.

My favourite-quotes file includes these about diary-keeping:

“I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read in the trains. – Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest

“… He wondered again for whom he was writing the diary. For the future, for the past – for an age that might be imaginary. And in front of him there lay not death but annihilation. The diary would be reduced to ashes and himself to vapor. Only the Thought Police would read what he had written, before they wiped it out of existence and out of memory. How could you make an appeal to the future when not a trace of you, not even an anonymous word scribbled on a piece of paper, could physically survive?” – George Orwell, 1984

The Orwell quote reminds me that nothing is forever. Other than the fanciful idea that a little bit of me could live on as part of a universal consciousness after artificial intelligence someday finds and absorbs my journal (along with everything else), I’m resigned to the reality that my diary will one day vanish.

Weighing in at about 4 million words – “and every one a gem,” I joke – I’d probably have to live to the age of 135 to distill it into the Great Canadian Novel, or even just something people would want to read. No matter. As Nin said, “We write to heighten our awareness of life,” and I think I’ve at least done that.

Some diarists’ words continue to speak to people long after they are gone, such as Pepys, Nin, Anne Frank, Virginia Woolf, Franz Kafka and Charles Darwin. I’d include on this list of famous people, someone named Jim, whose journal I chanced upon on a rainy day in a Montreal laneway two decades ago. It was uncanny that I, of all people, would find his diary, which dated from 1969 and contained lots of photos. In addition to sharing the same first name, we were both francophiles from Ontario who were born in 1948. After reading his journal I felt that I probably knew him better than even some of his friends and family members did – at least who he was in 1969 – because on its pages he poured out his heart about leaving home and living on his own. My initial efforts to reunite Jim with his diary went nowhere, but 20 years later, through internet sleuthing, I was able to contact his only sibling and get it to her. Jim, I learned, had died of AIDS in 1992, a decade before I found his journal.

“Reading the diary brings back so many memories,” his sister said. “I was very aware that he disliked school but had no idea how much and how depressed he was.”

***

It’s been said that when you keep a diary you are in a sense writing a letter to your future self. And now that I am my future self, I consult it much more than ever before. With aging, I’m losing friends and family members at an accelerating pace, and my journal helps evoke as vividly as possible memories of favourite moments with my favourite people. And as I time-travel through what I’ve written, I marvel at how unreliable my memory is, or has become. It’s shocking to discover how off the mark my recollections often are. Another revelation is how much time changes one’s perspective of things. What a difference a year can make. Issues that are mountains at one point in life are often molehills at another, and vice versa. Diaries have a way of letting you see the big picture and not fret so much over the small stuff.

My friend Michelle, who has been keeping a journal since she was nine, contends that we are different people at different times. I can see that. I think we evolve, but retain something of our core selves from the get-go. Our lives, at various points, are like variations on a theme – the theme being our unique selves.

Michelle was understandably shocked and saddened when her brother Chris died in May at age 63 and, before writing a beautiful warts-and-all tribute to her remarkable eldest sibling, she went back to the treasure chest that is her diary. Even her little-girl’s voice in her little-girl’s pink diary, railing about her big brother’s bullying, helped her appreciate their loving relationship and all its complexities over the years. “There’s something precious for me now in reading anything at all about Chris,” she said.

You lose someone you love and you want to hold onto every scrap.

Had I also kept a diary from the age of nine, I would know whom I should thank the most – Pete, Ralph or Wayne – for saving my life at the muddy swimming hole.

And I’d know so much more.

If I could write a letter to my nine-year-old self

it would simply say: “Start a diary.”

A joy to read, Jim. Glad someone is keeping score. A diary, as Gertrude Stein observed, "means yes indeed."